Individual ⊂ Collective

Conversations comparing the individual and the collective as frames of reference often become a confrontation of opposites. Opinions are categorized either pro collective or individualistic. In reality these extremes do not truly exclude one another. It is only the discussion that gets polarised. This text covers the relationship between the individual and the collective and the problems of the conversation. There is no collective without individuals – the team consists of individuals, so the individual and the team cannot be separate things. They are inseparable and complementary. In team sports it is the collective that is competing, not the individuals. The concept “team” includes the individuals, but also consists of their interactions and interdependencies forming a complex system. Individualism on the other hand does not put up well with the benefit of a collective.

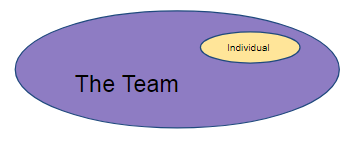

Figure 1. An individual is logically a subset of a team. The group “team” includes the individuals and thus is a wider frame of reference for understanding the whole. Looking at the actions of an individual only works in special cases and in sufficiently small details.

The goals scored in a match count for the team. Individual statistics are not the deciding factor for the result of the match (which team wins). Teams compete interacting with each other as whole systems. When a team wins, the individuals win. As the team develops, the individuals are also developing. Of course it is possible to win games without developing.

The complexity framework

Floorball is an invasion sport in which space and time are fundamental variables. They depend on the location and interaction of multiple players. Every player has an impact on the game situation and to possible solutions in the game. Simply the positioning of an individual player affects the spaces created on the field. In this sense, a true 1vs1 situation does not exist in an invasion sport.

Because of the interactions between the parts, the invasion game is defined as a complex system. These interactions allow the system to develop features that do not exist in individual parts of it. For this reason, the game cannot be deeply understood if these interdependencies are overlooked. The team (as well as the individual) is a complex system. Thus, neither the individual nor the 1vs1 situation cannot be isolated from the game environment if general conclusions of the game are to be made. Through the complexity paradigm, we seek to understand the game as a whole. This does not mean complication by adding variables, rather the game is explained by some simple principles – but in a different way.

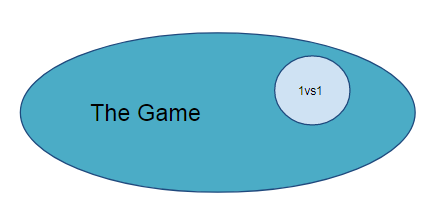

Figure 2. Logically, the "isolated 1vs1" in a big space is a subset (special case) of floorball. In majority of the situations, it is not sensible to ignore the interactions with the rest of the players.

There are situations in which a player faces an opponent in a large space, so that the interactions of other players with these two are weaker. In such a case, the interactions could be temporarily ignored. These are exceptions that emerge as a result of collective behaviour – not a starting point for analyzing the game. Ignoring the interactions between players should be justified with careful analysis.

An "isolated individualistic performance" does not exist in the game. Every action – even standing still – affects other players and the emergence of spaces in between. Just positioning oneself may be a vital contribution to the team's performance such as attracting the opponent's defender and making space for teammates. Playing floorball is collective action – the game happens between players. You cannot play alone.

How does all this influence our practice?

The frame of reference and the language we use, affect how deeply we understand the game. This directly affects our activities in everyday life. If we want floorball to evolve, we must try to look at it through a more modern lens. The framework of complexity takes into account the above-mentioned interactions and collective behaviour. Individuals are not removed from it, but placed in the context of the game.

"There's Nothing More Practical Than A Good Theory" -Kurt Lewin

Interactions between teams and players set their own expectations for the skills that the game demands from a player. Opponents constrain the actions of an individual player. She needs to react and anticipate opponents and teammates actions that form the dynamic game environment. Isolated physical or technical training do not include the psychological abilities of adapting to the environment, which are crucial in floorball. A player's skill is not about the ability to perform high-quality technical and physical actions alone. Those should be performed for a real reason and also adapted to the actual situation on hand. This requires constant perception of essential information in the middle of the chaos of the game. Collective training of tactical situations enables the learning of this. Perception is intertwined with action and thus translates to interaction.Emphasizing individual technique or skill over the whole skill eliminates alternatives, mistakes, chaos, and disturbances. This is against specificity of training. The player doesn’t learn to match perception of game information and the technical actions. On the other hand, individual technique and fitness, do not disappear from collective training. Instead they happen in a representative context. Volume and (relative) intensity of training are accumulated to a sufficient degree from playing exercises. We should be looking for the minimum effective dose of training load that keeps the players developing, especially at the youth level. Instead, currently the individual physical properties are maximized in a hurry comparing players quantitatively with others in the same age group. In worst cases it is the training load that is maximized.

Technique and fitness are subordinate to the tactical dimension, because they are always tactical in the context of a game – they affect the game situation. A player spends the majority of the game without the ball. Even the best players make mistakes that must be collectively reacted to. These skills must also be actively coached, not dismissed.

A game situation cannot always be solved by quantitative amount of technical skill or fitness. Adapting by performing a suitable action is critical. Forcing the play with weak decisions will cause problems even if the individual wins her direct 1vs1-situation. Often, it is necessary to feint and surprise the opponent as a collective as well as individually. A player could dribble towards a gap in the opponents defensive line to attract and move them, then pass to a space created behind the line. Our own team should be able to anticipate such collective actions somehow, supporting the dribbler and observing the new space. Technically and physically the solutions may be "creative" but they should somehow align tactically to common principles of play. When a ball crosses the goal-line in accordance to the rules of the game, the goal registered as a goal regardless of the technique. Coaching such principles of play instead of techniques alone, makes the game model flexible and forms a language of game actions.

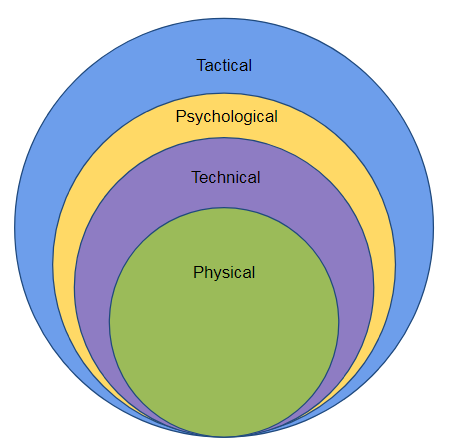

Figure 3. The best transfer-effect happens when training is designed taking into account all aspects of the game. First, choose the tactical goal and the moments of the game that you want to develop. After that, psychological training methods are planned, such as giving feedback and keeping score. Next come the optional added technical constraints and finally the physical demands by distribution of recovery breaks during the exercise. In Tactical Periodization methodology, training is designed in such hiearchy.

Players are communicating nonverbally in the game using floorball actions. The game model is their language. It must be flexible but clear enough. This needs a lot of focused training. An example could be as follows. The ball carrier dribbles, attracting one or two opponents towards the ball. He may keep them following until the pressure gets too high. This asks for support in certain available directions, and commands a possible teammate who is positioned on the way of the dribble to move and find space elsewhere. Clear principles create order in the chaos. A good team plays like "one organism", with fluent nonverbal communication. They form something of a ‘collective instinct’.

Training collectively in real game situations will afford the corresponding technical and physical (as well as psychologically competitive) repetitions without repetition. Traditionally, the technical skill of an individual is developed through the amount of repetitions of an explicit model technique. This is simply not how we acquire or perform skills. Even in very closed skill such as shooting, the skillful athletes technical details vary more than for the less skillful ones. Technique varies, but accuracy is better. A great shooter focuses on hitting the target, not how this is technically achieved. Variation is inevitable. In an invasion sport, adaptation and variation are manifold. Considering this in training design is critical.

Modern skill acquisition theory and the Constraints Led Approach

The design of modern skill training (Chow et al. 2016) implements the following starting points:

- The exercise must represent the competition.

- Manipulating the constraints will guide learning in the desired direction.

- Combining information and movement, that is, observing your body and the environment is central.

- Attention will be directed to the goal of the movement, not to the details.

Source: https://www.judolehti.fi/tieto-meema/millaista-on-fiksu-taitovalmennus-petteri-pohja-pohtii/ (finnish, sorry)

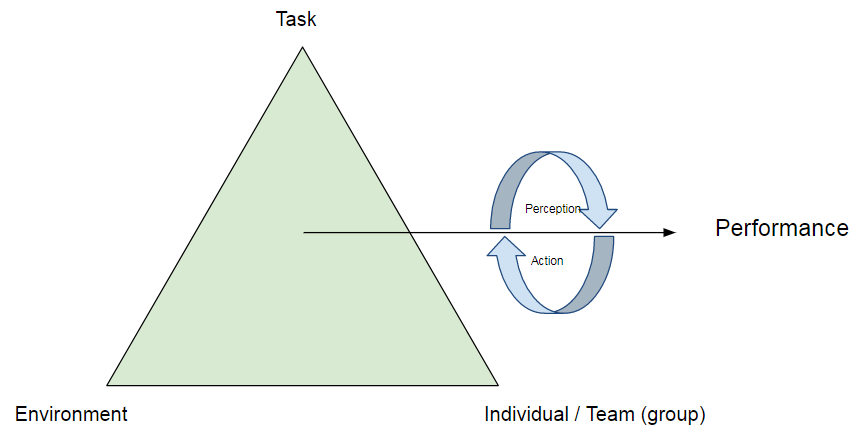

The above principles are based on constraints led approach (CLA) and non-linear pedagogy. These methodologies were strongly highlighted at the Scientific Conference on Motor Skill Acquisition during the Autumn in Kisakallio. According to CLA, an organism (an individual or a group) is given a task that is solved while adapting to an environment. The constraints create a space (the triangle), within which the organism begins to solve the motor problem, self-organizing its actions.

Figure 4. Visualization of the constraints led approach. The constraints create a space within which the organism continuously perceives the environment in order to match actions to the information of the situation. Perception and action are intertwined, not sequential steps during the process.

These contemporary theories of motor learning challenge our traditional concepts of learning. We do not act, learn or remember like a computer. The brain cannot store and retrieve countless different precise movement patterns from the memory and run them through like a script. Environment and context affect our memories. Techniques are not remembered, they emerge when an organism perceives the environment and matches its activity with the observed information. Perception is not just visual and conscious. It also happens through motion, proprioception etc. and is partly subconscious.

Performance depends on coordinating our actions with perceived information. What the player perceives is the meaning of a situation for herself. This means the opportunities for action (affordance) that are present in the game environment at a given moment. When action is intertwined with perception, the result is meaningful and the emotions are connected to perception-action. This way the instinctive, emotion-based decision making develops. Representative simulation of the game in training is a key factors in such implicit learning. The information, action and emotion from the observation are integrated during repetitions.

The theory is based on ecological psychology. Perception and action take place simultaneously in space and time, not sequentially. Perception is not just looking. It does not always happen consciously. Likewise, adaptation takes place in large part in the body and the subconscious (e.g. reflexes). Therefore, implicit learning in game situations is crucial. This differs essentially from the linear cognitivistic "perception, analysis, decision-making, excecution" view. Not every decision is conscious. We cannot stop and analyze the game while under time pressure. Locking up the technical solution in advance is also problematic. The opponent might step in in the middle of such decision making cycle. It is best to play “present in this moment" – using intuition and know-how to help when there’s no time for the conscious process.

Video. Movement helps observe things that would otherwise be missed. For example, a baseball catcher updates his running direction while catching a high ball. She does not run straight from the starting point to the ball landing position. "We must perceive in order to move, but we must also move in order to perceive" -James J. Gibson

The collective coaching model is individualistic as well

Closed-skill technique drills do not encourage or foster creativity. If each individual is meant to repeat the same pattern multiple times, the intention is the opposite – making clones out of the individuals. In the current floorball culture (at least in Finland), there is a tendency to emphasize the importance of players' creativity by downplaying tactics. It is deemed tactics that kill creativity – but for some reason this is not the case for one-size-fits-all technical training. Model techniques are taught in detail by the coach but making decisions or adapting to situation are assumed to come from “mothers milk”. The players are expected to choose suitable technical action from a library in their memory. Either you have talent or not.

In a tactical sense, a lot of responsibility for decisions in game is shifted to the individual instead of the coach. In a team training like this, the tactical culture and nonverbal communication might be poor, but the players survive with individual skills and self-organization. Tactics are explained, sometimes drawn on the fly during a match. Individual mistakes and attitudes become the most common problem in functioning of such team. Some players will of course learn to execute the coaches tactics somehow even during a match – or adapt to such difficult situation with their individual skills. The rest are given pressure to find ways to survive. This often leads to more comparison of players and less of coaching each individual with good effort.

Collective coaching gives individuals room and appreciates diversity. It does not try to copy existing top players based on individual skills or properties. When the method of execution is not predetermined, an individual may use her creativity to reach a tactical task. Everybody does not have to do the same, but every player needs to align to the team values, cooperation and game model. In collective coaching, a player is free to make "well-intentioned mistakes" – to play brave and to take risks within the principles of the game model. Reacting to the mistakes as a team is achieved by practicing different moments of the game – transitions included in the training. This is how the collective tactics encourage the individual to play brave and try new or difficult things.

A collective’s coach will pick suitable players – not just the individuals with best physique or technique. It gives players the chance to succeed by diverse individual means. If the game model is flexible, not every player needs to be physically or technically peaked. They just need to learn to solve situations for the benefit of the team. A game model also helps team-building. Everyone is asked to play along common principles but not using the same technical-physical means.

This is also an important question of values in junior sports. Are we trying to find talent or develop it? Do we keep as many young players playing and participating as possible, or do we clean up the lesser material at an early age? Can we really predict by monitoring and testing individuals out of context to find out who will later become top players – in the context of the actual game? Is individual skill somehow different from the skill of playing the game floorball?

Antti Hänninen ( @AjHanninen )

Further reading:

Fergus Connolly: Game Changer

Kelso & Engstrøm: The Complementary Nature

Davids et al .: Dynamics of Skill Acquisition: Constraints-Led Approach

Tech metaphors are holding back brain research

My previous blog on the definition of 'technique'

Emergence and self-organization by Esko Kilpi https://medium.com/@EskoKilpi/emergence-and-self-organization-ecb9a1810baa

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/320741853_Creative_Motor_Actions_As_Emerging_from_Movement_Variability