There is an ongoing dispute in finnish floorball discussion on the future of finnish floorball and the coaching policies of the federation. We have been writing against the oversimplified view of the game as multiple 1vs1-situations. There are ways for the abstraction of the game using the different moments of the game and the areas on the field. The selection of the viewpoint directly affects the interventions that the coaches choose to improve the team and individual players. How we see the game is an important coaching-philosophical choice: do we see the game as a whole complex system or do we simplify it in a linear fashion into separate parts – neglecting the interactions.

Invasion team sports are games of space and time. Those are variables that depend on the interactions of multiple players. Every action of an individual player (including the actions without actually moving) become interactions with the environment and the rest of the players on the field. Playing is interacting, not just being athletic or having capabilities.

The more we focus on separate actions, the more responsibility is left to the players to learn the correct moment for each action. Using training time out of the team floorball sessions to train actions without game context costs valuable time from this learning process unless they are rigourously justified as steps of this learning. A floorball coaches responsibility is also to actively teach the players how to interact – that is to actually play floorball better. The least she can do is to provide an environment for the players to learn it themselves.

An individual player cannot properly learn the complex skill of a team sport as homework, alone. The opposite would be much more logical: use the team training time to maximally improve the interpersonal coordination of the team by training floorball interactions. Interaction includes action, so this time is not taken away from individual technique development either. The players could then perform supplementary training to hone their technical and physical skills alone or together during their own time. Even better if they have the opportunity to play street games and hone their skills in a game environment.

Motor learning theory and floorball interactions

Often we hear the argument that a player first needs to learn the movement patterns and repeat them until they are filed in the "muscle memory". Only after this is she able to perform them under pressure in a game context. This is the case according to contemporary motor skill and motor learning theories. It is very much possible to learn new skills in a game situation. That is how children also learn – by playing. People do not work like a machine: storing action scripts in their memory and running them at a correct moment. Instead we learn to adapt into a sport-specific environment. Technical details are variable, even though the repetitions have similar features. Our bodies have much in common after all. For example, players learn to deliver the ball to her teammates in variable situations. The players have individual differences in their passing and shooting techniques – or even better, they have totally different strengths and weaknesses. This is true even on the top level. According to complexity framework, such diversity is an advantage for the system.

During a “holistic” learning process of playing the game, technical and physical qualities are also challenged and improved in an integrated training approach. The physical intensity of a game-like exercise may sometimes be even higher than of the competition because of more recovery during the training session. Controlling the demands of an exercise might happen by varying the size of the playing area, recovery breaks and the number of teammates and opponents. This also varies the type of the physical stumulus of the session.

Interpersonal coordination

The individuals of a team always interact and (self)organize in order to cooperate – even when the team did not deliberately train tactics for every game situation. This is called interpersonal coordination. Skilled individuals might be able connect with their teammates in smaller space, less support and generally in more challenging situations. That is, during less organized moments. However, improving the coordination of a team is not exclusive to improving the individual. The players get physical and technical repetitions during game-like training. Training in representative game situations may then be better use of the time. The coach controls the technical and physical demands of the training, providing suitable technical and physical stimuli but the aim is also for the interpersonal system to learn to coordinate better. Such approach also makes the technical and physical training specific and the transfer of training more likely.

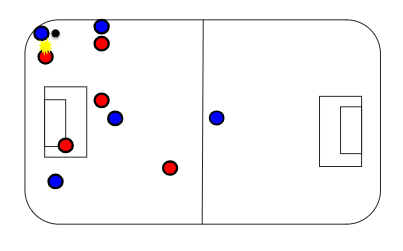

Figure 1. The blue team ball carrier is under pressure and might lose the ball. He does not have many good passing options or space to dribble into. In case of negative transition, the blue team defensive balance is off and they would most likely suffer a dangerous counterattack.

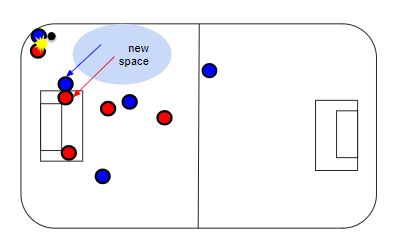

Figure 2. The blue team has organized their offensive play and have better structure. With a simple movement, a teammate might be able to create space for the ball carrier to move into. Also the rest of the blue players offer more support to and all the while the blue team also has a better balance in case of a negative transition.

As the previous figures demonstrate, by organizing the team better during the offensive moments it is possible to perform better even when the ball carrier has problems maintaining possession under pressure, in a small space. Creating space by movements off-the-ball and having a balanced positioning may help the team thrive even if their player do not have the skills to dribble past good defenders in a small space. In situations like this it would be easy – but lazy – to blame it on the individual who was not technical, strong or fast enough to win her "1vs1". This conclusion would lead in different interventions than explained above.

Implications for training are the use of realistic game situations, either specific to the problematic situation or general game-like training where the players learn to solve similar situations. Some examples were shown in a previous blog.

An example: Indidual or interpersonal?

The finnish federation has used the following video clip to demonstrate that the mens national team players lack linear speed. The situation builds from poorly executed offensive moment and a high pressing defensive moment after that. Sweden is able to play out of pressure, making the pass to Svahn who gets the ball into slightly ahead of Piha. Now the situation is 3vs2 for the swedish team with the right lane defender having a problematic body shape and being unable to pressure Svahn. It ends up in a dangerous 2vs1 for Sweden.

Video 1. This example was also discussed in Perttu Kytöhonka’s earlier blog.

In my own recent blog post I analyzed the finnish teams high pressing during the EFT tournament. It is interesting to note that similar problems seem to occur even with a fast player like S. Johansson trying to maybe a bit slower player like J. Samuelsson:

Video 2. FIN-SWE 0-4 goal from the most recent EFT tournament

Now it depends on the coaching philosophy if you believe it is the best approach to pick faster players to the national team, get the chosen players run faster – or train the team with the tactical intention of organizing these moments of the game at least slightly better at the same time (having the players train situation-specific individual qualities at the same time)?

Adopting the complexity lens will imply the nature of the game is about interpersonal coordination – floorball interactions. This means the team is trying to accomplish tactical tasks with variable means but according to shared team principles. The principles create options for the players to choose and help them self-organize (choose suitable options) to solve the game situation themselves.

This approach reduces the need of finding the individual culprit who gets the blame for causing a problematic situation – as long as the whole team plays according to the team principles. Organizing the offensive moments keeping in mind the possible negative transition (and preparing for it) also empowers the ball carrier to challenge herself without the fear of failure in case of unsuccesful dribbles for example. Such approach is beneficial especially for a developing or a youth team.

Antti Hänninen (@AjHanninen)

Further reading: Mark O'Sullivan's great blog. He spoke about football interactions in the second scientific conference on motor skill acquisition in Kisakallio (november 2017).